Intel’s NUC Extreme mini PC kits have always been hard to recommend. It’s true that they’re considerably smaller than even the smallest mini ITX PC cases; it’s impossible to fit this much performance into less space if you’re using general-purpose PC components. But they’re also expensive, they haven't been as fast as standard desktop PCs, and their upgradability has been limited. Those three things essentially defeat the purpose of building a beefy desktop gaming PC or workstation.

Codenamed “Dragon Canyon,” the newest version of the NUC Extreme Kit helps to fix the latter two problems by switching to actual socketed desktop processors rather than soldered-in laptop versions. It’s still an expensive box—you’ll pay about $1,150 for a Core i7 version with no RAM, SSD, GPU, or operating system and $1,450 for the Core i9 version we tested—but its performance now comes much closer to that of a typical desktop.

The NUC Extreme still isn’t for everyone, but if money is no object and you want the smallest desktop you can get, the 12th-gen NUC Extreme is less of a compromise than the previous versions were.

Design and upgradability

The external design of the NUC 12 Extreme case, which uses 12th-gen Alder Lake CPUs but is the third generation of NUC Extreme hardware, is nearly identical to the previous version. It’s a long, narrow computer with mesh panels for ventilation on the top and sides and a neon skull LED on the front (all of the system's LEDs can be customized or disabled entirely with Intel's NUC Software Studio app). The only change from the 11th-gen NUC Extreme is that one of the USB-A ports on the front has been exchanged for a USB-C port.

The 8-liter enclosure’s volume compares favorably to notable mini ITX cases like the second-generation NZXT H1 (15.6L), the SSUPD Meshlicious (14.7L), and the Cooler Master NR200P (18.5L). The downside is that you can’t use a standard motherboard or CPU cooler in the NUC, though it does appear to use a normal 650W SFX power supply that should be easy to replace if it breaks or if you need to replace it with a higher-wattage model. Your GPU options will also be relatively limited—Intel’s NUC case can take cards up to 12 inches long, but you’ll be limited to dual-slot cards. We tested ours with an Asus Dual GeForce RTX 3060 GPU installed, and while larger cards can fit, you definitely won’t be able to cram most Radeon RX 6900 XT or RTX 3080 models into it.

The 12th-gen model’s internal design is also similar to the previous model’s, so much so that you could upgrade the previous enclosure with the newer Compute Element board if you bought it separately. Intel’s Compute Element board and your GPU both plug in to a daughterboard at the bottom of the case, allowing them both to sit parallel to one another without requiring the use of flimsy or finicky PCIe riser cables.

One welcome internal change to the NUC is that it now uses socketed desktop processors that can be pulled out and replaced, whereas the 11th-gen model used a soldered-down laptop CPU. This is presumably because Intel has finally moved its desktop chips to its more efficient 10 nm manufacturing process; the NUC’s small size and limited cooling capacity would have been a bad fit for the hot and power-hungry 14 nm 11th-gen desktop chips, so Intel opted to use a 10 nm 11th-gen laptop CPU with the power limits turned up instead. An actual CPU socket will be particularly handy if 13th-gen Intel CPUs continue to be compatible with the LGA1700 socket and 600-series chipsets.

For a computer this size, the NUC Extreme has plenty of ports, including an SD card reader and one USB-A port. On the front, it has one USB-C port; on the back, it has six USB-A ports, one HDMI port, 2.5Gbps and 10Gbps Ethernet ports, and two Thunderbolt 4 ports. The Thunderbolt and HDMI ports can be used to drive displays if you don’t have a GPU installed or if you want to hook displays to both the integrated GPU and the dedicated GPU. This is a narrow use case, but being able to connect half a dozen monitors to a PC this size makes it a pretty flexible workstation.

Wi-Fi 6E and Bluetooth 5.2 are integrated on the board, courtesy of Intel’s AX211 Wi-Fi chipset, and the NUC has two slots for PCIe 4.0 NVMe SSDs and a pair of DDR4 SODIMM slots for user-replaceable RAM. We could ding the NUC for going with DDR4 instead of DDR5, but DDR5 is still much more expensive and much less available than DDR4 while offering only marginal speed benefits. This will change over time as DDR5 gets cheaper, faster, and more plentiful. But for now, going with DDR4 instead is the more practical decision.

The whole enclosure can be disassembled with a Phillips-head screwdriver. To access the internals, you pop the back panel off, slide off the side panels, and carefully lift the top panel up (it has fans in it, so it doesn’t totally disconnect from the rest of the case without additional effort). As super-small desktop PCs go, it’s easy to work on, if only because the enclosure doesn’t let you install big, complicated coolers or a rat’s nest of fan and LED cables.

Performance

We compared the NUC 12 Extreme to its immediate predecessor with the same RAM and GPU installed to test the direct generational improvement, and we’ve also compared it to a Core i7-12700 PC we’ve been testing to see how well it stacks up to a typical custom-built desktop with additional cooling capacity. Here are the full specs for reference:

- A NUC 12 Extreme with a Core i9-12900 CPU and 16GB of 3200MHZ DDR4 RAM.

- A NUC 11 Extreme with a Core i9-11900KB CPU and 16GB of 3200MHz DDR4 RAM.

- A Core i7-12700 in an Asus B660-Plus D4 motherboard with 64GB of 3200MHz Corsair DDR4 RAM. We tested this configuration once with the CPU set at Intel's default power settings (a PL1 value of 65W and a PL2 value of 180W), and once with Asus' default performance-boosting settings enabled (a PL1 value of 165W and a PL2 value of 241W).

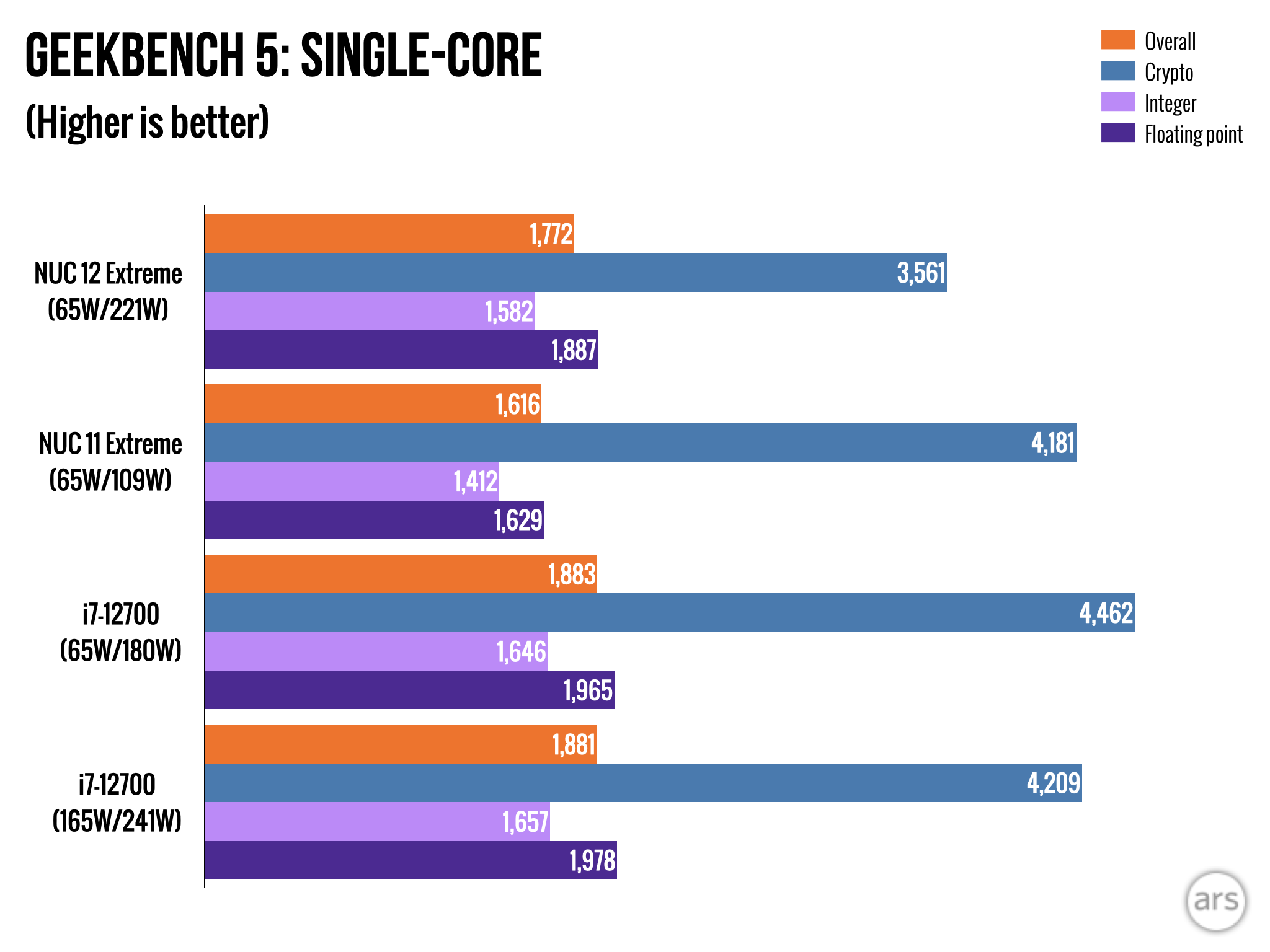

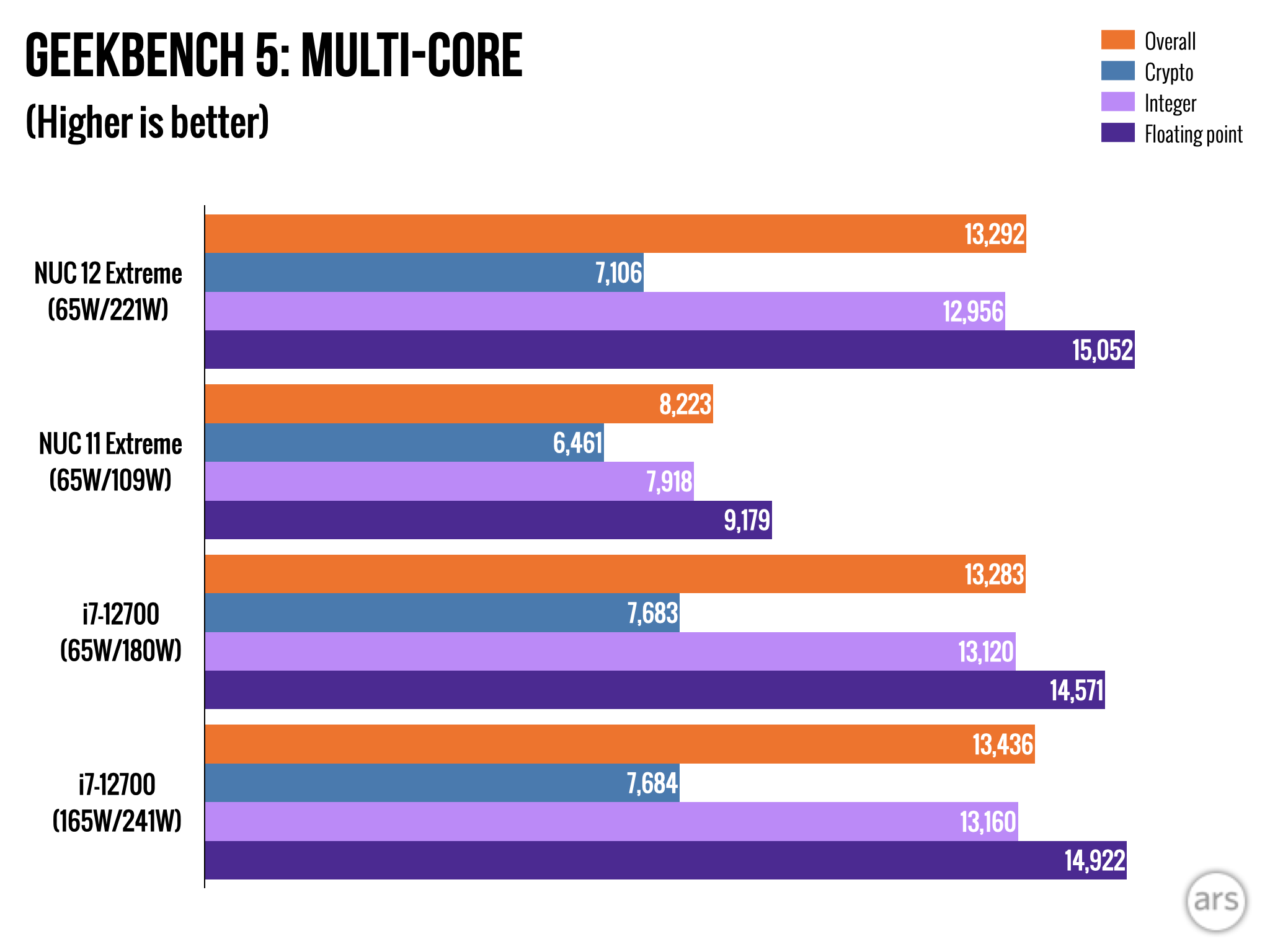

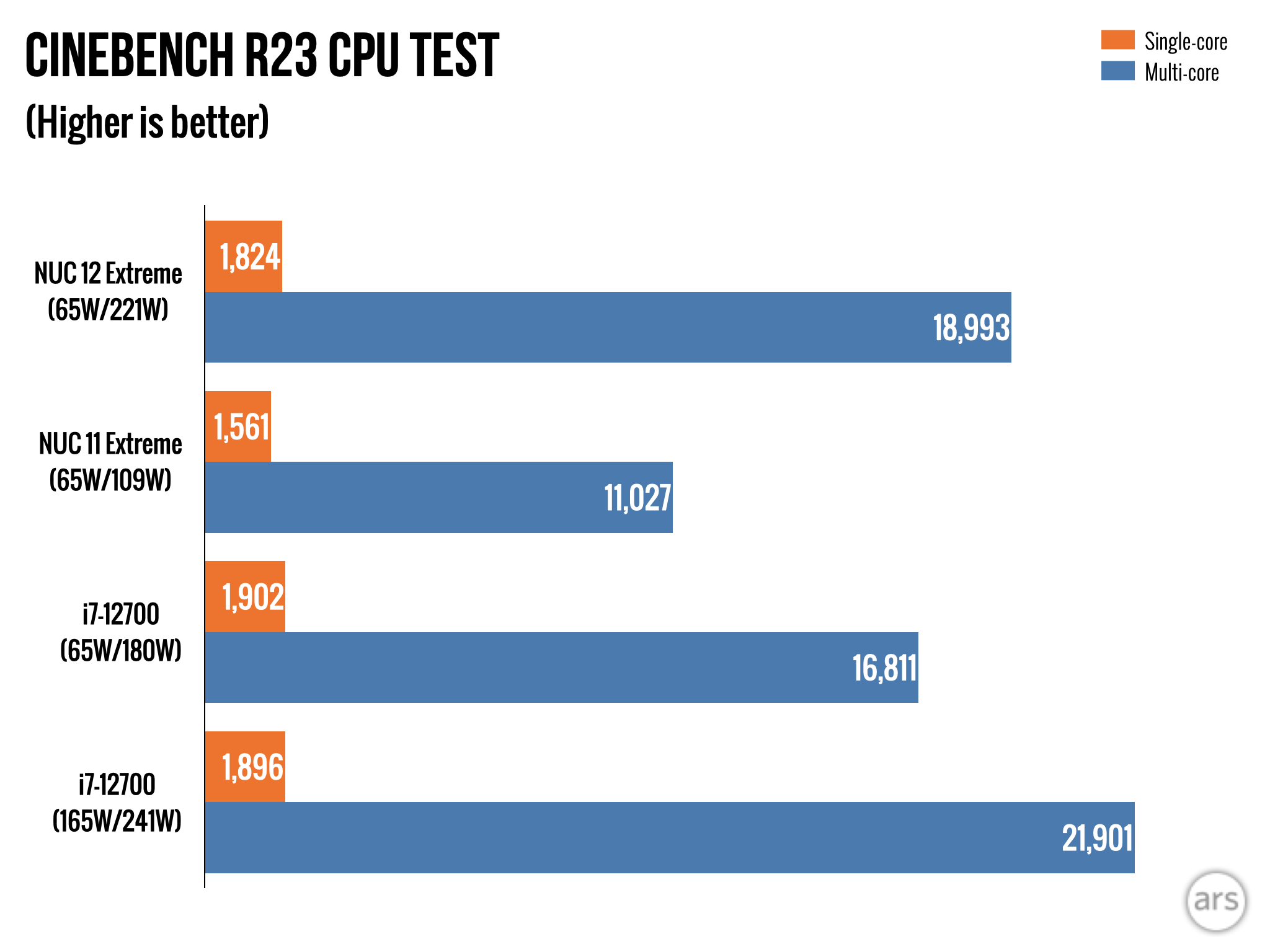

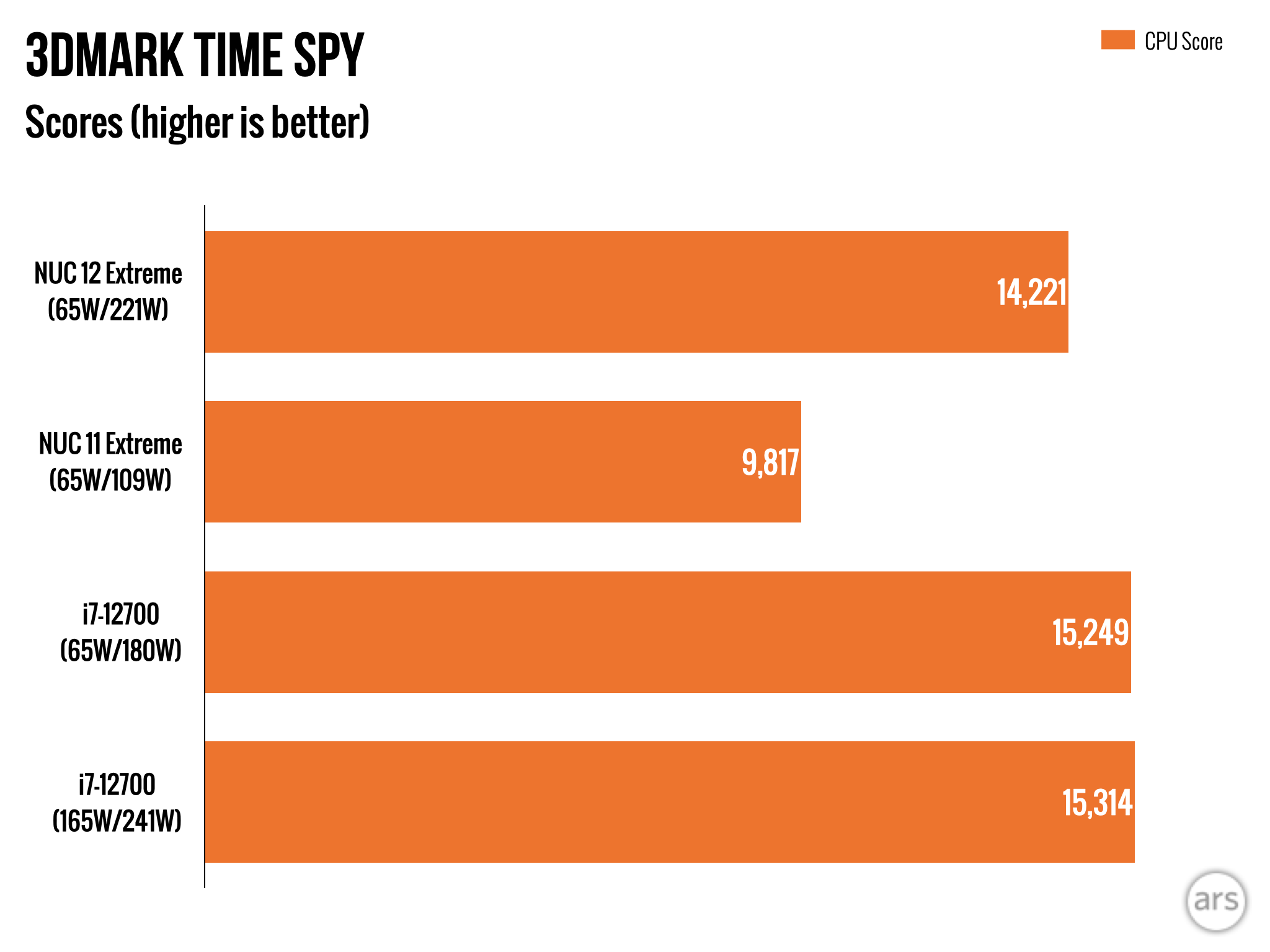

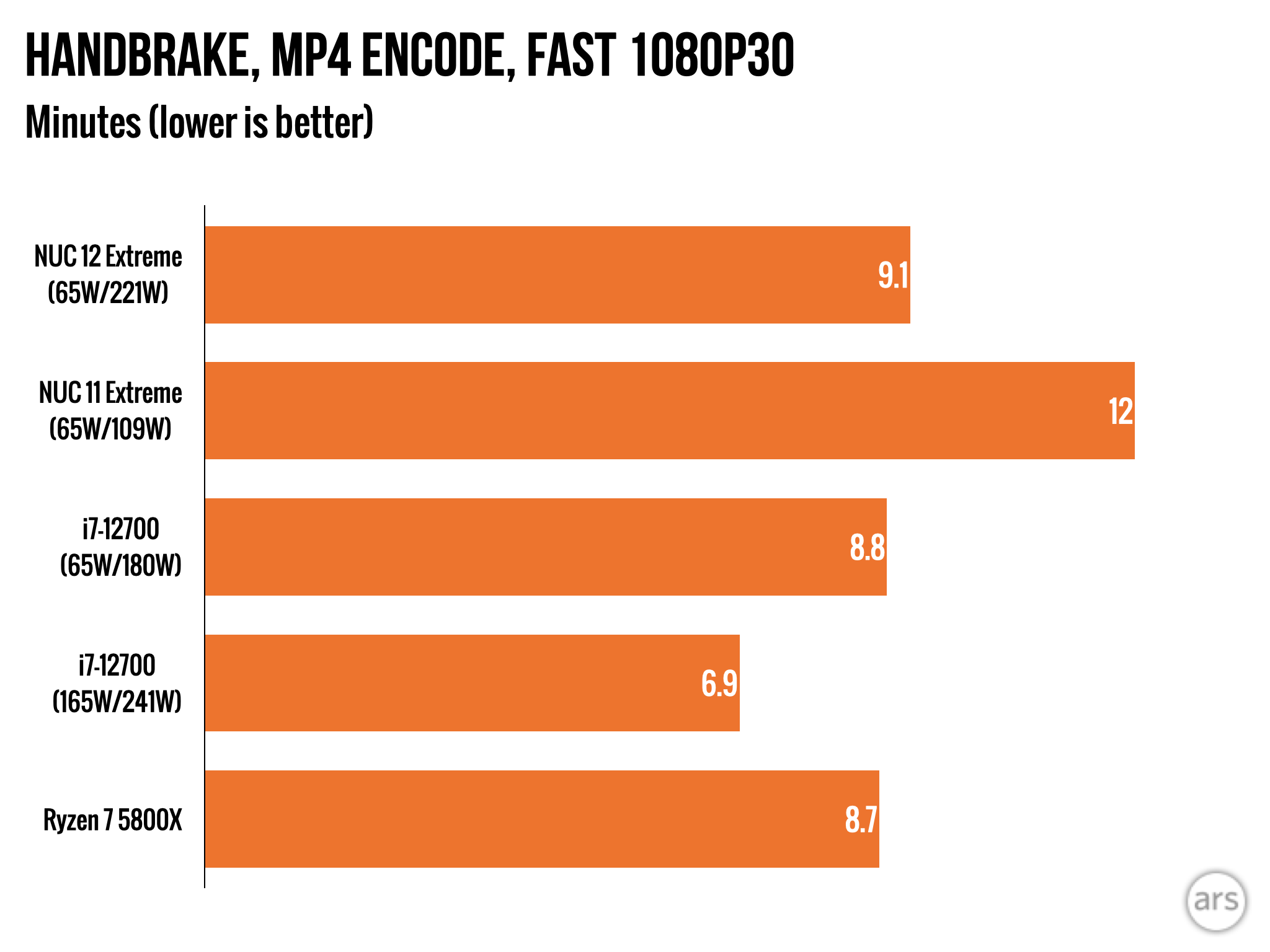

We’ll explore Intel’s power settings in greater depth in another article, but for both NUC boxes, we stuck with their default “max performance” power settings in the BIOS. For the NUC 11, this sets the CPU’s long-term power consumption (PL1) at 65 W and its short-term power consumption (PL2) at 109 W. The NUC 12, meanwhile, has a PL1 of 65 W and a PL2 of 221 W. Thanks to its extra cores and increased power, the NUC 12 excels at both lightweight tests like Geekbench and more sustained workloads like our Handbrake video-encoding test and Cinebench.

Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham

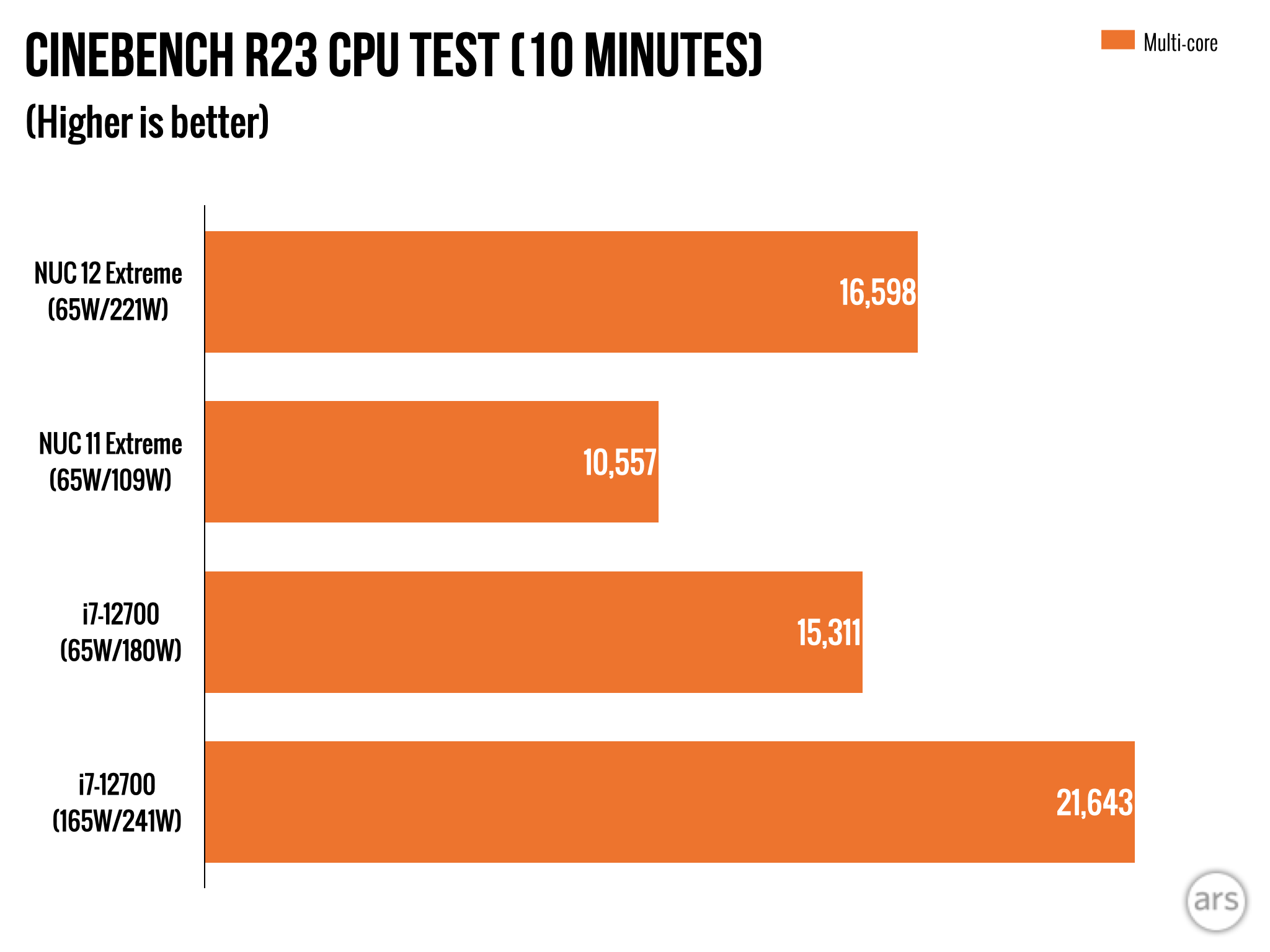

But a custom-built desktop will still have the performance edge. Even though it’s a little slower and has four fewer E-cores than the NUC’s Core i9-12900, our Core i7-12700 PC was able to keep pace with the NUC 12 in most of our tests at Intel's default power settings, including both Geekbench and the Handbrake encoding test. Once we raised the power limits using our Asus motherboard's automated performance-boosting settings, the Core i7 managed to pull ahead, thanks to its bulky tower cooler. You can bump the power levels of both the NUC 11 and the NUC 12 to try to squeeze more performance out of them, but thermal throttling will kick in before you see much of a benefit.

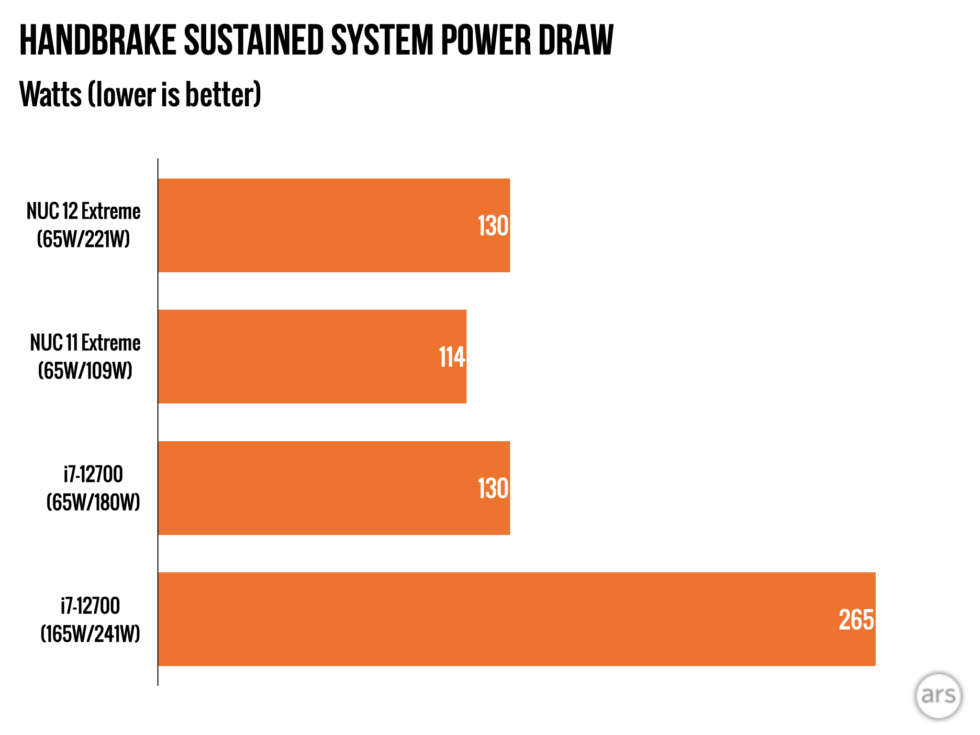

That extra performance does come with increased power usage. During our Handbrake video encoding test, the NUC 12 consumed around 15 W more power at the wall than the NUC 11 system. But the chip is still more efficient overall—that’s a roughly 13 percent increase in sustained power consumption for a 32 percent increase in performance. And with its power limits removed, the Core i7-12700 PC consumes twice as much power as the NUC.

Tiny, pricey powerhouse

A custom-built desktop, even one built in a mini ITX case, will still be able to deliver better performance than the NUC 12 when paired with a larger air cooler or an AIO watercooling loop. That desktop will also probably be a few hundred dollars cheaper than the NUC, and it will give you more flexibility when you're choosing a GPU.

All of that said, the NUC 12 performs a whole lot better than the NUC it replaces, partly because of Alder Lake’s architectural improvements and partly because of the CPU’s extra E-cores. Using Intel’s default power limits also makes it pretty efficient when running at full tilt. And it’s great to finally get a NUC Extreme Compute Unit where the CPU can be upgraded without needing to replace the entire board.

Past NUC Extreme Kits were difficult to recommend because they came with too many trade-offs. The NUC 12 Extreme still comes with compromises compared to a mini ITX desktop PC, mostly in the form of a lower performance ceiling and a higher price. But the performance gap is a lot smaller than it was, and the NUC is only around half the size of a great small-form-factor PC case. If you’re looking for a tiny gaming desktop or workstation, it’s at least worth a look.

The good

- Great performance and efficiency compared to the NUC 11 model it replaces

- Socketed desktop CPU creates an easier upgrade path

- Easy to access the dual M.2 storage slots, DDR4 RAM slots, and GPU slot

- Plenty of ports, especially for the size

The bad

- Modest fan will keep it from running as fast as a full-size desktop with more cooling capacity

- Limited to dual-slot, 12-inch-long GPUs at a time when buying a specific GPU is incredibly difficult

- Skull LED won’t be to everyone’s taste (though you can turn it off)

The ugly

- Still several hundred dollars more expensive than a mini ITX desktop PC

Ars Technica may earn compensation for sales from links on this post through affiliate programs.

Listing image by Andrew Cunningham

https://ift.tt/19KnJ4o

Technology

No comments:

Post a Comment