A small retail business in North Africa, a North American telecommunications provider, and two separate religious organizations: What do they have in common? They’re all running poorly configured Microsoft servers that for months or years have been spraying the Internet with gigabytes-per-second of junk data in distributed-denial-of-service attacks designed to disrupt or completely take down websites and services.

In all, recently published research from Black Lotus Labs, the research arm of networking and application technology company Lumen, identified more than 12,000 servers—all running Microsoft domain controllers hosting the company’s Active Directory services—that were regularly used to magnify the size of distributed-denial-of-service attacks, or DDoSes.

A never-ending arms race

For decades, DDoSers have battled with defenders in a never-ending arms race. Early on, DDoSers simply corralled ever-larger numbers of Internet-connected devices into botnets and then used them to simultaneously send a target more data than it could handle. Targets—be they games, new sites, or even crucial pillars of Internet infrastructure—often buckled at the strain and either completely fell over or slowed to a trickle.

Companies like Lumen, Netscout, Cloudflare, and Akamai then countered with defenses that filtered out the junk traffic, allowing their customers to withstand the torrents. DDoSers responded by rolling out new types of attacks that temporarily stymied those defenses. The race continues to play out.

One of the chief methods DDoSers use to gain the upper hand is known as reflection. Rather than sending the torrent of junk traffic to the target directly, DDoSers send network requests to one or more third parties. By choosing third parties with known misconfigurations in their networks and spoofing the requests to give the appearance that they were sent by the target, the third parties end up reflecting the data at the target, often in sizes that are tens, hundreds, or even thousands of times bigger than the original payload.

Some of the better-known reflectors are misconfigured servers running services such as open DNS resolvers, the network time protocol, Memcached for database caching, and the WS-Discovery protocol found in Internet of Things devices. Also known as amplification attacks, these reflection techniques allow record-breaking DDoSes to be delivered by the tiniest of botnets.

When domain controllers attack

Over the past year, a growing source of reflection attacks has been the Connectionless Lightweight Directory Access Protocol. A Microsoft derivation of the industry-standard Lightweight Directory Access Protocol, CLDAP uses User Datagram Protocol packets so Windows clients can discover services for authenticating users.

“Many versions of MS Server still in operation have a CLDAP service on by default,” Chad Davis, a researcher at Black Lotus Labs, wrote in an email. “When these domain controllers are not exposed to the open Internet (which is true for the vast majority of the deployments), this UDP service is harmless. But on the open Internet, all UDP services are vulnerable to reflection.”

DDoSers have been using the protocol since at least 2017 to magnify data torrents by a factor of 56 to 70, making it among the more powerful reflectors available. When CLDAP reflection was first discovered, the number of servers exposing the service to the Internet was in the tens of thousands. After coming to public attention, the number dropped. Since 2020, however, the number has once again climbed, with a 60-percent spike in the past 12 months alone, according to Black Lotus Labs.

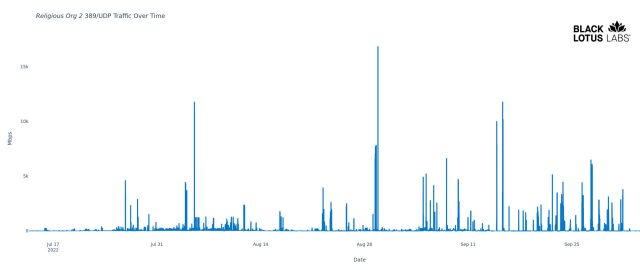

The researcher went on to profile four of those servers. The most destructive one was affiliated with an unidentified religious organization and routinely generates torrents of unthinkable sizes of reflected DDoS traffic. As the following figure shows, this source was responsible for numerous bursts from July through September, with four of them exceeding 10Gbps and one approaching 17Gbps.

“This traffic is perhaps strong enough to DoS some less well provisioned servers all by itself,” Davis wrote in his report. “In theory, a hundred of these, working in unison, could generate a Terabit per second of attack traffic.”

Besides exposing CLDAP to the Internet at large, Davis said, the server also has an open DNS resolver that can be abused for reflection, and it has an exposed vulnerable SMB service. It also sends bi-directional communications with confirmed control servers for multiple malware families.

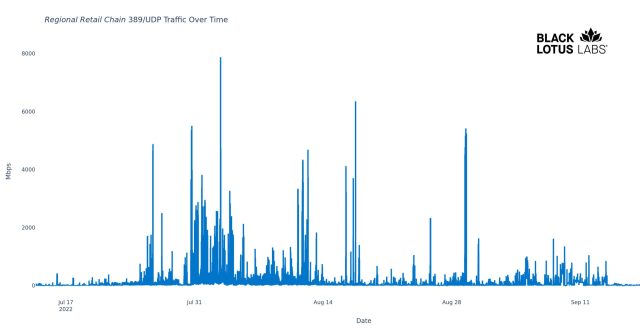

A second profiled Microsoft server was also affiliated with a religious organization, this one in North America. Over an 18-month period, it has delivered peak bit rates of more than 2Gbps. Like the other religious organization's server, it also had an open DNS resolver and served as a bot for multiple malware families.

Davis went on to discuss a CLDAP service hosted on an IP address associated with a telecommunications provider in North America that has been delivering potent DDoSes for more than a year. Some of the regularly changing targets are hosted on a single IP range. In other cases, the target is an entire network prefix.

Last was a server associated with a regional retail business in North Africa. For more than nine months, Black Lotus Labs has observed it repeatedly DDoSing an array of targets, with peaks of 7.8Gbps. Like the two religious organizations' servers, it exhibits signs of being exploited by malware. It’s also exposing vulnerable remote desktop and SMB services to the Internet.

“Trying to build a story out of these facts leads us to see this system as the MS Domain Controller in a small organization,” Davis wrote. “Small sites might only have a single data center, and they would also likely host SMB, DNS, and RDP. Additionally, it’s inherent that smaller organizations, on the whole, will have less sophisticated security practices, thus suggesting more likelihood of being infected with bot malware.”

Davis said that Black Lotus was able to further confirm all four servers were engaged in actual DDoS attacks by analyzing the targets on the receiving end of the data torrents. In an email, Black Lotus Labs said it was able to confirm all 12,142 servers identified as CLDAP reflectors as Microsoft domain controllers by analyzing their response to LDAP pings, which included communications through the expected port (389/UDP) and the expected number of bytes.

Reining in CLDAP

Active Directory is among the only Microsoft products to include CLDAP. Even then, the implementation is limited to a single command—the LDAP ping. Davis wrote:

This command is not a directory-related command; it’s used by Windows clients attempting to discover a service via which they may authenticate users. While it’s hard to imagine why someone would design their network topology such that a client would need to discover a local authentication service over the open Internet, it happens. The motivations of the deployment are less salient than the simple fact that, when exposed to the public Internet, the service is open to reflection.

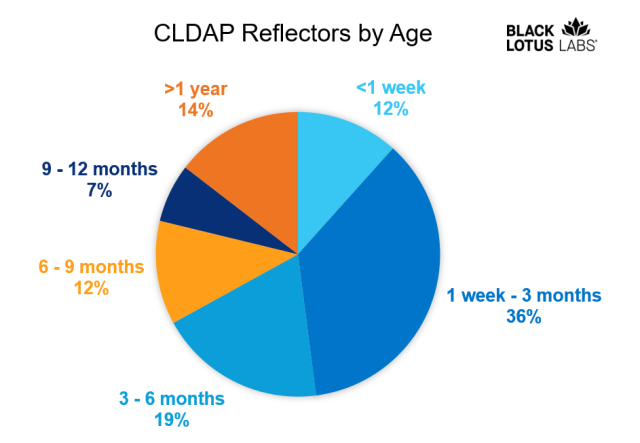

One interesting observation is that anomalous spikes increased in frequency the longer a CLDAP reflector remained open. “This makes sense as we would expect that attackers would need some time to locate new reflectors and update their arsenal,” Davis wrote.

Black Lotus Labs provided the following advice for locking down servers running Directory:

- Network administrators: Consider not exposing CLDAP service (389/UDP) to the open Internet.

- If exposure of the CLDAP service to the open Internet is absolutely necessary, take pains to secure and defend the system:

- On versions of MS Server supporting LDAP ping on the TCP LDAP service, turn off the UDP service and access LDAP ping via TCP.

- If MS Server version doesn’t support LDAP ping on TCP, rate limit the traffic generated by the 389/UDP service to prevent use in DDoS.

- If MS Server version doesn’t support LDAP ping on TCP, firewall access to the port so that only your legitimate clients can reach the service.

- Network defenders: Implement some measures to prevent spoofed IP traffic, such as Reverse Path Forwarding (RPF), either loose or, if feasible, strict. For more guidance, the MANRS initiative offers in-depth discussion of anti-spoofing guidelines and real-world applications.

The post said Black Lotus Labs notified operators of the misconfigured CLDAP services in the IP space provided by Lumen. The company is working to notify other operators and possibly begin blocking long-lived CLDAP reflectors on the Lumen backbone. Microsoft had no immediate comment for this post.

https://ift.tt/PwMkK8G

Technology

No comments:

Post a Comment